Archie Bunker and performance practice

Musical Hermeneutics (part 7)

Paul de Man uses this example from All in the Family to make the following statement:

...asked by his wife whether he wants to have his bowling shoes laced over or under, Archie Bunker answers with a question: "What's the difference?"... As long as we're talking about bowling shoes, the consequences are relatively trivial; Archie Bunker, who is a great believer in the authority of origins (as long, of course, as they are the right origins) muddles along in a world where literal and figurative meanings get in each other's way though not without discomforts. But suppose that it is a de-bunker rather than a "Bunker," and a de-bunker of the arche (or origin), an archie Debunker such as Nietzsche or Jacques Derrida for instance, who asks the question "What is the Difference"--and we cannot even tell from his grammar whether he "really" wants to know "what" the difference is or is he just telling us so we shouldn't even try to find it. (de Man 368)

Aside from the brilliance of wit (and it’s even more clever if you know a little about Derrida and “différance”), de Man’s point is that texts remain opaque. Archie is saying, “What’s the difference” in a rhetorical fashion. He means, “Who cares?” Edith reads it literally and begins explaining the difference between lacing over and under which is intolerable to Archie. Edith’s response to Archie’s rhetorical question infuriates him because it’s the opposite of what he meant. de Man uses this example to show that the rhetorical and the grammatical can’t be separated textually. The text can always be read in multiple ways — especially by a “deBunker.”

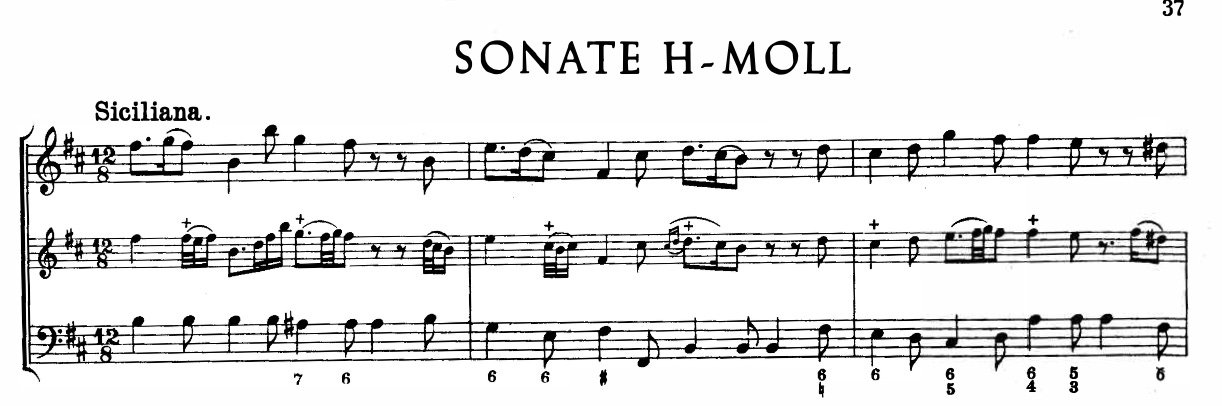

In music, we can imagine similar scenarios where a text is taken literally when it shouldn’t be. The humor of Baroque Sonate doesn’t match that of Archie’s bowling shoes, but the issue is the same. Take this Telemann sonata:

The top line is what Telemann wrote in the score. The second line is Telemann’s example of how he might play that top line. In this case, a grammatic or philological reading of the text would result in a drastically different performance. In fact, a literal rendering would seem to be the opposite of what Telemann wanted. One can easily imagine a fastidious and too eager student playing Telemann’s realization as if that was what Telemann actually intended. In this case, the difference is pretty huge, Edith, but you can’t get out of the problem by taking Telemann’s written improvisation as a new Urtext.

In the case of the Telemann Sonate, the difference is stark, but are other musical factors — let’s say with tempo or volume — that different? If you play a ländler waltz in strict tempo, you are really substituting a philological reading of the tempo for the “intended” result. We can drill down even further. A crescendo written in a certain measure can be read strictly starting and stopping under the notes where it is inscribed or it can be generally applied. Interestingly, it can’t be read literally for volume in the same way. We don’t have an accurate way to define what a crescendo from mp to mf means, but let’s go beyond the problems of intentionality. (See some of the previous posts in this series for the problems with the “intentional fallacy.”)

Borrowing an example from Paul Fry, if we assign a class the “God is dead” passage from Nietzsche’s “The Gay Science,” we will likely have to do a little philological work for modern audiences and explain that “fröhliche” in German has nothing to do with LGBTQ issues and that the use of “gay” in the translation has to do with a 19th century understanding of the English word. However, a modern reader might say, “Wait a minute. We actually might be able to gain some insight into our current situation if we read it as “gay” in the modern sense. Indeed, it might become even more meaningful that way, and we might even gain some philological insights on why the word “gay” was adopted for minority communities in English.

Most music students are surprised to discover that in Leopold Mozart’s violin treatise’s list of tempo descriptions, Vivace is listed as a slower tempo than Allegretto which is slower than Allegro, ma non tanto, which is slower than Allegro.

Of course, a quick search asking if Vivace is slower than Allegro gives me this:

What happens when a modern readers says, “Wait a minute. What if we read it with our modern understanding of Vivace. Can’t we gain new insights by taking it faster? Is there any reason to take it slower because Leo Mozart told you to?”

The truth is, there might be a good reason to listen to uncle Leo. It might turn out to be more expressive a little slower, but then we are basing our decisions on how it is the most expressive to us rather than the intentionality of the composer or the practice of the time.

I would argue that this is, in fact, what we are doing all of the time as musicians. It’s just that some folks make an appeal to a historical argument to give the patina of humility. It’s as if they are saying, “Well, if it were up to me, I would play it differently, but Uncle Leo says I have to play it slow, and this isn’t about me. It’s about my uncle Leo.” And I would simply say in response in all seriousness, “What’s the difference?”

Often we are talking about context I think. Am I teaching a piece of music for the purposes of public performance, historical practice/ perspective or other purely educational reasons, or for pure enjoyment? There is a ton of value in working towards the intended goals of the composer as best as we can determine them, especially if they are dead. But then there is also value in allowing the music to speak to modern musicians (students or professionals) and ease up on the the "correct historical performance practice" in favor of a performance that more embodies the ensemble making the music.

This has similar resonances throughout the history of philosophy and theology. Much of Aristotle’s and Plato’s writings are for facilitating further dialogue and exploration, in Aristotle’s case this is more muted in the texts we read due to the “genre”. Aquinas wrote assuming the in-class disputatio as the text’s partner. We then read these works to find “Aristotle’s theory” or the authoritative “Thomistic” answer, and in doing so we’re putting the text to our uses which may deviate from their “intended” use.